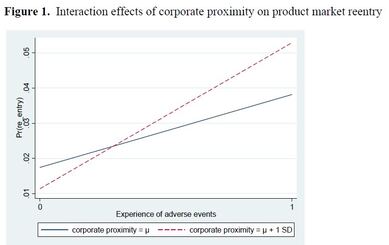

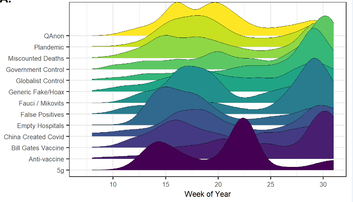

Our economy and society are currently seeing a big change. Many firms are replacing the traditional management practices of supervision, goals, and managed rewards with a market turn that exposes workers to the risks and rewards of competitive markets. This is seen in many places, from the “contractors” delivering meals or transportation services under app platforms all the way up to investment bankers taking a cut from each deal. Do we know what this does to people? We do not, which is why research like Alexandra Michel’s recent publication in Administrative Science Quarterly is important. She looked at bankers’ transition into market-exposed roles, which usually happens after 9 years of employment. What she found was remarkable, because it demonstrated that moving from managed rewards to market rewards is a radical change that alters the mind and body of the worker. Why is that? Think about what life is like for most workers in regular organizations. Their role is defined, their goals are defined, and the work is structured by supervisors or pre-defined organizational processes. It is a predictable life. If they have contingent rewards or incentives, the goals to fulfill have been specified in advance and the resources to reach the goals are in place. At most, things could be unpredictable because managers rank workers, so the rewards to one depend on the others. Still, this is a pretty predictable life. Market-exposed work is different. The role is to meet demand in whatever form the demand takes. The Uber driver (for example) needs to be in the right place at the right time. The investment banker needs to bring the parties of a potential deal together, so they agree on the terms. This is an unpredictable life. Effort and rewards are no longer connected as well because the market is unpredictable, and there is little reward outside that given by meeting demand. And strangely enough, although highly contingent rewards in conventional organizations make people work hard, the market turn makes people work harder simply because there is always one more potential, but uncertain, reward that seems to be within reach. The result is overwork. And more importantly, unlike the managed employees, the market-exposed employees mostly blame themselves. After all, they are entrepreneur-like in job description and should be designing work so that they actually meet market demand. Business failure is personal failure, both in their mind and in those of their colleagues, who subscribe to the same belief system. The solution is obvious. They need to manage their body and their mind in order to be strong enough for the overwork and stress of their role. And this is where it gets scary. The bankers Michel studied read about medical drugs of various kinds and made liberal use of doctors who would give them the medications they asked for. Some of them even found foreign mail-order suppliers of drugs that would enhance the performance of the mind, or conceal fatigue, or handle various medical breakdowns. Because body failure meant business failure, they manipulated their bodies. Incentives are supposed to be good for organizations, and market incentives especially so because they allow worker and organization to completely agree on what should be done. Only now are we beginning to understand that they can also be exceptionally harmful for the worker. Michel, Alexandra. 2022. Embodying the Market: The Emergence of the Body Entrepreneur. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  We all try to learn from our failures, and we believe that we usually do so successfully. Similarly, we often think that firms can learn from failures, and this belief is shared by people who observe (and work in) firms and those who study organizational learning. It may be shocking to realize that some of the details on whether and how firms learn are not well documented. For example, we know that firms will change something after experiencing failure, but we are rarely able to measure whether they change the right thing and whether the change is an improvement. This is why research by Cheon Mok (John)Kim, Colleen M Cunningham, and John Joseph published in Academy of Management Journal is interesting. They checked whether medical device firms could distinguish between failures caused by product features or market conditions and found that they could. So far so good. They also checked whether failures due to product features led to re-entry with a new product, and this is where things got more complicated – and interesting. The answer is yes, but not always. More importantly, the researchers could distinguish the conditions that made such learning more likely. If the business unit that withdrew a failed product was close to the corporate headquarters – geographically, in the organizational hierarchy, or in product lineup – then it was more likely to re-enter with a new product. What is so distinctive about being close to the corporate center? One feature is attention and surveillance; another is support and resources. These seem like heads and tails of a coin, and clearly either one could have this effect, and most likely they act in concert. In fact, the findings were even stronger for the more repairable types of failures. If the failure was distinctly from the product design, not the user, then corporate proximity had greater effect. If the product failure was severe, then corporate proximity had greater effect. In both cases, the fault is more obvious and more easily traced to the firm, and accordingly it should be easier to learn from failure. And learn they did. This is important knowledge for two reasons. First, although we often assume that learning from failure happens, it is often the case that the very things we assume to be true are faulty in some way, and need to be checked carefully. That is also true about learning from failure, because the conditions that make it happen are not always present. The firm with highly decentralized management that is also geographically dispersed and diversified has three strikes against learning from failure. There are many such firms. This brings us to the second point. From what we know about learning, we should also be able to design organizations that learn well. Given how learning is related to connections within the firm, and the attention (and surveillance, support, and resources) that follows, designing firms with structures that fail to learn is a completely unnecessary error, especially given the costs of simply giving up when re-entry with an improved product would have been possible. If we know how firms learn, we can design them to learn well. Kim, Cheon Mok (John), Colleen M Cunningham,and John Joseph. 2022. Corporate Proximity and Product Market Reentry: The Role of Corporate Headquarters in Business Unit Response to Product Failure. Academyof Management Journal, forthcoming.  I am sure you have read the news about how a variety of COVID-19 conspiracy theories have persuaded many people that the pandemic is a fake and manipulative scam, possibly involving a disease no more harmless than flu. Or the ones saying it is a deadly attack weapon designed by some secretive perpetrator. Maybe you have also thought about how this is a modern phenomenon, driven by domestic and foreign manipulators exploiting the easy access to social media. And surely you have felt sorry for the people who believed that Covid was harmless and ended up sick because they failed to protect themselves. But this story is only half true. The pandemic is new and the specific conspiracy theories are new, but conspiracy theories of various kinds are a permanent feature of our society. People share variations of them in face-to-face conversations, in writing, and now also on social media. Who are these people spreading conspiracy theories? Why do they do it? In research published in American Sociological Review, these issues are explored by Hayagreeva Rao, Paul Vicinanza, Echo Zhou,and me. Conspiracy theories make threats more understandable, and thereby give a feeling of mastery and control. This may seem ironic because conspiracy theories always involve some hidden plot by secretive perpetrators. That’s exactly the point though. The conspiracy theorist is the one who can see through the concealment and understand the plot. And sometimes the plot means that the apparent danger is not real (the scam disease). Even when the danger is real (the disease as weapon), some people will find the thought of a human attacker more comfortable than that of a mindless virus feeding on people to reproduce itself. How do we know that conspiracy theories help people cope with the pandemic threat? Simple. One of the drivers of social media Covid conspiracy talk was the infection rate. More infection, more conspiracy theory talk. Conspiracy theories counter threat and reduce fear. Conspiracy theories have moderate and extreme versions. This is easy to tell by looking at their content. The “film your hospital” conspiracy theory was about hospitals pretending to be filled with patients (for money, or for political reasons). This is moderate. An example extreme version is Bill Gates orchestrating the pandemic for various evil purposes. Another is Covid being a way of controlling people while constructing malicious 5G towers. Why does it matter that the conspiracy theories differ in how extreme they are? Simple, again. One of the drivers of social media Covid conspiracy talk is that the moderate versions are gateways that get people into conspiracy talk. Later many of them graduate to extreme versions. Conspiracy theorists can spread different conspiracy theories, often at the same time. And remarkably, often conspiracy theories that contradict each other. Logically, Covid can’t both be a harmless scam and a deadly weapon, but the same people would spread both within the span of a week (and yes, these were people, not bots – we can identify bots). How to make sense of this? Maybe the best way to sum it up is that conspiracy theories are a form of reality denial. When the reality is threatening and difficult to explain and rationalize, as it is during a pandemic, a conspiracy theory offers an escape. But the escape is not perfect, because our society is full of people who don’t believe in conspiracy theories and will challenge the believers. That’s why some poeple have multiple conspiracy theories. Whenever one of them is challenged, the conspiracy theorist can fall back on another. What to do about such reality denial? The starting point must be that it is not simple ignorance. Reality denial is motivated reasoning, and facts alone will not help. Explain how one conspiracy theorist is false, and the conspiracy theorist will fall back on another. Because it is motivated by a wish to reduce and control threat, the solution always involves explanation of how the threat can be reduced through human action. It is a difficult conversation because masks, isolation, and vaccinations all have this effect, but conspiracy talk does not go away unless we explain how the threat can be reduced through joint action such as vaccinations and personal caution. Greve, H. R., Rao, H., Vicinanza, P., & Zhou, E. Y. (2022). Online Conspiracy Groups: Micro-Bloggers, Bots, and Coronavirus Conspiracy Talk on Twitter. American Sociological Review, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224221125937  In the ideal world, we would like firms to make a profit and also to help the environment and society. Indeed, the turn toward ESG (environment, social, and governance) evaluation of firms is evidence that this is important to many, including a growing niche of investors who favor firms that are responsible as well as profitable. Are we living in this ideal world already? Or if not, are we moving toward it? The answers are not clear. In a recent article in Administrative Science Quarterly, Ben W. Lewis and W. Chad Carlos looked at how firms reacted to being rated as charitable. Being rated as charitable is supposed to be good, both because it means that they contribute to the social dimension (the S of ESG) and also, indirectly, that they are profitable enough that they can afford to do so. Many firms cannot. If we lived in the ideal world combining profits and ESG, or even a more limited world combining profits and social contribution, managers would savor such a rating and continue making philanthropic contributions. But in fact, firms rated as charitable reduced their philanthropic contributions. How can this be? To begin with, we can dismiss the idea that firms don’t care about ratings, because there is much evidence that they care and that they try to get high rating outcomes even it is costly to do so. If high ratings matter and executives decide to avoid a high rating outcome, something else is at work. The explanation has two parts: competing logics and reactivity. Competing logics exist when firms are rated – or more broadly, evaluated – on multiple criteria, and these are backed by different groups with conflicting interests. For firms, the main group that executives worry about are shareholders, of course, and their interest in maintaining steady profits and investments in gaining future profits. The logic in this is how firms can accomplish the valuation increases and dividends shareholders crave. Through this logic, money given away to philanthropic contributions is just like money invested to protect the environment that does not also increase productivity. It not only reduces current valuation increases but may also hold back investments that would help future valuation increases. From the shareholders’ point of view, this is bad even if the ability to fund charity signals current profits. What about reactivity? This part is easy to explain. Executives have many reasons to make philanthropic contributions, including the obvious one that they personally want to make societal contributions using firm resources. But executives also know that they are monitored by shareholders and financial analysts. If their contributions are so high that they are labeled as “nice” by a ratings agency, they may be targeted as acting contrary to shareholder interests. It is much better to make contributions that are small enough to be below the radar, so they react by reducing contributions. It may seem like a reverse form of impression management that executives try to avoid a high rating of the firm, but it simply reveals that the most important audience for impression management is shareholders. How big and important were these effects? Quite big. The ratings agency studied was KLD, which is a major rater of firm social contributions. Following a positive rating, firms reduced their philanthropic contributions by about one-half of a percent of profits, which is one-third of the average difference between firms rated positively and firms not given a positive rating by KLD. Simply put, the firms reduced contributions exactly as much as needed to become rated as less charitable the next year. We know that firm decision makers care about their reputation, engage in impression management, and pay attention to ratings. To observe reactivity like this is a clear signal that we do not yet live in an ideal world in which firms can divide attention between profits and ESG criteria, and we do not even know whether we are moving in that direction. Time will tell. Lewis, Ben W., W. Chad Carlos. Avoiding the Appearance of Virtue: Reactivity to Corporate Social Responsibility Ratings in an Era of Shareholder Primacy. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Gender pay gap disparity – paying women less than men for comparable work – is widespread and unfair, and much attention is given to how to remove it. Perhaps the most prominent option is to require pay gap disclosure, so that firms paying women less will be revealed and their reputation harmed. The idea is of course that two things will happen – firms will act to improve their reputation through paying women more, and female job applicants are warned and can stay away from these firms until conditions improve. The US has been reluctant to mandate transparency, but thanks to pay transparency laws elsewhere, we now know more about its effects. In a recent publication in Administrative Science Quarterly, Amanda Sharkey, Elizabeth Pontikes, and Greta Hsu studied the effects of mandated publication of the gender pay gap in the United Kingdom. One piece of good news: firms with pay parity received a temporary improvement in employee evaluations when that information was made public. One piece of bad news: that was the only good news. In particular, firms with pay disparity showed no observable short- or long-term decline in employee evaluations, and hence suffered no reputation loss either. Failing to find an effect was not a result of data problems; nor was it inconsequential. The authors were analyzing Glassdoor evaluations, which are reviews of each firm anonymously posted by its employees. Each evaluation is accurately timed, so it is easy to match the evaluation with the disclosure of the pay gap. The evaluations are consequential because many potential job seekers check Glassdoor reviews, both the numeric evaluations and the written text. This is a puzzle, and Sharkey, Pontikes, and Hsu proceeded to look for explanations. Interestingly, although some explanations could be excluded, not a single explanation could account for the failure to shame the firms with a pay gap. Part of the reason is that there are simply too many possible explanations, and they probably work together to make this happen. Because they add up to letting firms get away with unfair payment, it is worthwhile listing three explanations as warnings. Pay attention! There is some evidence that employees don’t fully pay attention to the pay gap when assessing their own workplace. Extending that observation, it is fair to wonder whether potential job applicants pay enough attention too. Paying attention is the first protection against walking into a trap. Interpret information! There is some evidence that employees react less when the pay gap is obscured by job heterogeneity. That is natural, but also discouraging, because more deliberate and conscious interpretation would usually help them understand that they are in a pay disparity trap. Act on interpretation! There is some evidence of resignation, with employees not reacting to the pay gap because they have become used to it. That is exactly how traps work – people do not escape from them. The reason to list these warnings is that it is hard to think of any policy to reduce the pay gap disparity that would be more effective than disclosure. Organizations constantly need to recruit new employees, and they always worry about their ability to attract the best. Obviously so, because there is another pay gap that is much more logical and beneficial for the organization than the gender pay gap. There are few jobs in which the pay gap between the most and the least productive employee is so great that the organization does not care about employee quality. The most productive employee is usually so much better for so little extra pay that having all the potential stars apply – male and female – is a great benefit for the organization. If employees and job applicants pay attention, interpret information, and act on the interpretation, pay disparity would simply be too costly for the organization. Perhaps they will gradually learn to do so. Sharkey, Amanda, Elizabeth Pontikes, and Greta Hsu. 2022. "The Impact of Mandated Pay Gap Transparency on Firms’ Reputations as Employers." Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming Photo credit.  Let’s start by acknowledging that top-division professional sports players and coaches make very intelligent decisions – probably better than many corporate managers. After all, they drill and execute similar scenarios over and over again while facing adversaries who are familiar with their every move. So, let’s drop the “dumb jock” stereotype and admit that football, like soccer, has the same (or fewer) decision-biases and misjudgments as those we would see in a non-sport organization. They can teach us a lot about decision making. In particular, fourth-down plays are very instructive because they are when a football team either kicks the ball away or decides to “go for it” and try to gain enough yards to keep possession of the ball. It is an excellent context for examining how people handle risks and rewards, and Xavier Sobrepere i Profitos, Thomas Keil, and Pasi Kuusela took advantage of this in a recent article in Administrative Science Quarterly. Their idea is simple and novel. It is well known that people consider the risk of gains and losses from their decisions, and mentally they overweigh losses. It is well known that performance feedback on goals affects organizational decisions, so changes and risk taking are much less acceptable when performance is high. Putting these two together, every decision has content (risks and returns) and context (performance relative to goals). These two are usually considered separately, but actually they work together like two blades of a scissors. How does that influence fourth-down decisions? This is where the sophisticated, but still biased, decision making comes into play. Potential rewards are important but not always important: short fourth downs make teams more likely to go for it, but the difference is much bigger in the second half of the game. Goals are important but not always important: teams that are behind in the score (especially more than 10 points) are more likely to go for it, but the difference is much bigger in short fourth downs. And in fact, all of the effects listed here are bigger when the team has advanced beyond the middle of the field, so the opposing team’s endzone is close. To someone who follows football closely, this may seem to make a lot of sense, leading to the question of whether there is any bias here at all – isn’t this completely rational? No, it is not. Even when making risky decisions that are essentially random, potential gains and losses should not be seen as less important when performance feedback is positive. Gain, loss, and risk should not become less diagnostic in such a decision context, but football plays clearly show that they are. And football is a game against an adversary, so a tendency to go for it more often in a specific decision context is an easy “tell” that the opposing team can use to adjust their defense. The same is true outside the world of sports. Perhaps the most important part of performance feedback theory is not how organizations search for alternatives and make changes when performance is below aspiration levels. It is the opposite – how they fail to do so when performance is above aspiration levels. If managers are like these football teams, even known information about opportunities – similar to a one-yard fourth down on the opponent’s 20-yard line – may not be seen as diagnostic enough for their decision. After all, they are meeting their goals. This selective decision making, with performance feedback having an important effect in directing attention towards or away from opportunities, is the true bias revealed by the fourth-down plays. It is one that managers should pay attention to, and so should all those who teach management. Sobrepere i Profitos, Xavier, Thomas Keil, and Pasi Kuusela. 2022. The Two Blades of the Scissors: Performance Feedback and Intrinsic Attributes in Organizational Risk Taking. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Organizations have rules, employees who break rules, and rules on how to punish employees who break rules. Often these are thought of in simplified terms as ways of making transgression costly so that employees will not transgress. The simplification is silly – we know that transgression occurs anyway, so it is necessary to think more broadly about punishment rules. If the organization keeps the transgressor in employment, can it also manage a rehabilitation that ensures good work relations and avoids repeated rule-breaking? How can this be done? Surprisingly, these questions have not seen much investigation despite their obvious importance. But thanks to Erin Frey, Ethan Bernstein, and Nick Rekenthaler we now have research on this topic based on a military school (let’s call it the Academy) that has an honor code, cadets who break it, and a particular rule on how to punish those it retains because the violation is not too severe. The rule is interesting because it requires violators to wear a pin on their lapel indicating a rank one level lower than the lowest regular rank in the Academy for a period of many months. Given the military obsession with rank and alertness to symbols of rank, this marks them to everyone as having transgressed the honor code. In short, they are “screw-ups,” and everyone can see it. To an observer with some interest in history, this resembles a variety of medieval punishment methods meant to stigmatize violators and isolate them from their village, town, or city neighborhood. Stigmatization, whether intended or not, is generally quite effective in isolating individuals, attracting disdain, and preventing cooperation with others. So, can such a mark help rehabilitation? There is a key difference between a village and an organization, and maybe especially an educational organization. Organizations have clearly defined boundaries, so it is obvious to all that the marked transgressor is still a member. Organizations have interdependent tasks, so the marked transgressor needs to communicate with others, and vice versa. This creates opportunities for explaining the transgression, expressing regret, and showing recovery. Arguably the marking of a transgressor also creates a need to explain, express regret, and show recovery. The marked transgressor will be a stigmatized member rather than a regular one, so there is a social pressure to show signs of rehabilitation. In the Academy, there was an expectation that the marked transgressors should advocate and display even higher standards of behavior than others, and indeed they did so. How general is this effect? Here we need to speculate a bit, but some boundaries seem obvious. What about marking transgressors in customer-facing work? I would be uncomfortable seeing a barista with a mark indicating some sort of transgression. Even more so an airline pilot. Indeed, the uniforms used in many kinds of customer-facing work (again, all pilots and many baristas) are supposed to create generalized trust that does not single out anyone as being better or worse than others. Still, even if the effect of marking violators as a path to rehabilitation is not fully general, it is very interesting that it is possible. Organizations are hierarchies that can punish and try to rehabilitate through rules and hierarchical approaches, but they are also social systems. The marking of violators makes use of this and has an effect that is surprisingly beneficial. Frey, Erin, Ethan Bernstein, and Nick Rekenthaler. 2022. Scarlet Letters: Rehabilitation Trough Transgression Transparency and Personal Narrative Control. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming. Questions are great. Sometimes I get asked questions that stimulate ideas that I would not have thought of otherwise, and that lead to research. When the editors of the 20th anniversary special issue of Strategic Organization asked me to write about the relation between the Behavioral Theory of the Firm and Strategy, it made me wonder whether there was something special about the match between this theory and this field of research.

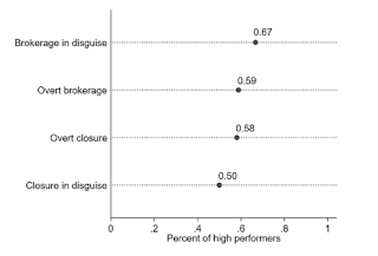

Why this question? The behavioral theory of the firm fuels an active and growing research agenda found mainly in organization theory, but also with much important work in strategy. So, it is possible that we can simply stand by and let things develop on their own, and the synergies between research in these two fields well take care of the rest. Yet somehow, that did not look like the right answer. The reason is that the basic interests of the fields of strategy and organization theory are different. Obviously not, because that is why they are different fields. To the Behavioral Theory of the Firm, this may not seem to matter because theory is about the mechanisms that drive outcomes in the world, not about the outcomes. It matters for research, though, because different outcomes can be studied depending on the interests of a field. This is a good reason to think of how the Behavioral Theory of the Firm and Strategy relate to each other. The result of our thinking was a series of questions on how strategy is shaped by the mechanisms in the behavioral theory of the firm. This is the right approach because the Behavioral Theory of the Firm is made for explaining what a firm – or any kind of organization – will do. So, it is the kind of theory that can be used for explaining the origins and changes of firm strategy. There are already partial answers to all of these questions, but still a lot of room for progress. The very short answer is that we developed a framework organized around how strategy is shaped by the 1) organizational structure, 2) organizational decision-makers, 3) organizational history, and 4) organizational environment. The Behavioral Theory of the Firm has useful ideas in each of these factors. The (slightly) longer answer? Please look for it in the short essay coauthored with Cyndi Man Zhang. Greve, H.R., C. Zhang Man. 2022. Is there a Strategic Organization in The Behavioral Theory of the Firm? Looking Back and Looking Forward. Strategic Organization, forthcoming.  As anyone in business will testify to, personal connections matter a lot for success. They are the source of information and ideas, they can be used to draw in resources and capabilities, and they give rise to yet more connections. The naïve version of this narrative is that more connections are always better, but we know that’s not true. Personal connections are maintained through attention and care, so having too many means neglecting many. Instead, what matters most is to be connected to people who are not connected to each other: to be a broker of personal ties. The network of a broker is the most efficient one for drawing in novel, timely, and helpful information, among other things. Except that being a broker is not a fail-safe path to success – we know it often does not work. Explaining when it works, and when it does not, was the goal of research done by Alessandro Iorio and published in Administrative Science Quarterly. His idea was simple and novel. Maybe I will see brokers as slightly suspicious characters because they know so many people I don’t know? Maybe as a result, I will hold back the information, resources, and network ties that I would otherwise provide to my contacts who I do not see as being brokers? Making this simple idea especially neat is that I may not be right about who is a broker and who is not. Accordingly, being a broker who is not perceived as a broker is great; such brokers in disguise get all the benefits. Not being a broker but being perceived as one is a disaster; their personal connections have a poor structure and are poorly fed with information. Iorio went ahead and tested this idea by getting data from a consulting firm and by doing experiments. The conclusion? Consultants who were brokers in disguise were clear winners in the ratings for being top innovation performers; two-thirds of them achieved this rank. Meanwhile, being a broker while being perceived as one was no better than not being a broker and not being perceived as one either. Brokerage works when it is hidden; not otherwise. Why is that? When gauging the effect of trustworthiness of each person, it became clear that being thought of as a broker meant being seen as less trustworthy. This explained brokers’ inability to take advantage of having better personal connections than other consultants. What does this mean for how we deal with personal connections in our career and life? Turning this evidence into advice is complicated. The benign version would be that modesty is a virtue, because dropping names of people others do not know places you at a disadvantage whether or not you really know them. The less benign version is that the successful user of personal networks is fundamentally dishonest because this person gives the impression of having a different network of contacts than the actual one. Of course, we should not be too surprised by this kind of problem. The behaviors that evidence shows to be effective when managing other people are not always the most admirable ones. Iorio, Alessandro. 2022. Brokers in Disguise: The Joint Effect of Actual Brokerage andSocially Perceived Brokerage on Network Advantage. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  The creative arts are full of one-hit wonders who produce exactly one famous hit and are never heard from again. Most famously this happens in music, but it is also true for authors, visual artists, and performing artists. Is it possible to predict which creative artists can have multiple hits? The usual answer is, “Of course not!” But if it were possible, such knowledge would be useful outside the arts as well. Organizations of all types often need to develop novel and creative products, and even those products that involve engineering or science ultimately start with creativity. Actually, we are making some progress in understanding how multiple hits are created. Research by Justin M. Berg published in Administrative Science Quarterly looked at musical artists and discovered that a key factor in becoming a multi-hit artist is the music made before the first hit. This sounds strange but is easy to explain. Before the first hit, artists are generally ignored and can freely choose what to create, and they may end up making choices that differ a great deal from each other. After the first hit, they are under the magnifying glass of the world (and themselves) and typically try to stay in tune with what their audience wants without changing too much from their past production. Problem is, what their audience wants keeps changing. This is where the production before fame becomes important. Some musicians make very novel music, some musicians make a great variety of music, and some musicians make music that lacks novelty and variation but hits exactly what the audience wants at the moment. Who can repeat the hits? When the question is phrased this way, it seems clear that variation is a good thing because it lets the musician adapt to new trends without changing too much from past work. That’s exactly what the research found. But interestingly, novelty before becoming popular also let the musician produce multiple hits. Maybe that’s because it creates a sense of freedom and an audience expectation of some surprises? But wait, before we worry about how a musician can get multiple hits, maybe we should think about how to get the first hit. So here is some bad news: Novelty is great for multiple hits but bad for getting the first one. Fortunately, the same is not true for variation, which helps the chances both for a first hit and for multiple hits. Of course, if you are an artist, you know that variety is a very hard thing to achieve, maybe even harder than novelty. In fact, the main driver of variety seems to be repeated failure when doing the same thing over and over again, illustrating that it is not just hard to accomplish but also hard to attempt. Cost and benefit… What do these findings on musicians tell organizational decision makers? More than you might assume. First, we know that creativity has similar effects on innovative work across a wide range of products, so we can actually learn about product design from successful musicians. Second, these findings directly tell us what resumes should look like when hiring someone to do development work – look for variety! It is valuable and costless, because job applicants will come with a great variety of variety levels. Finally, and this part could be costly, the findings also tell us what type of workflow a development team should have. Unlike musicians and other creative artists, who are forced by their audiences to stay relatively close to their past production, development teams will maintain a variety of projects if they are told to do so. And we know that variety increases the likelihood of success. Berg, Justin M. 2022. One-Hit Wonders versus Hit Makers: Sustaining Success in Creative Industries. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed