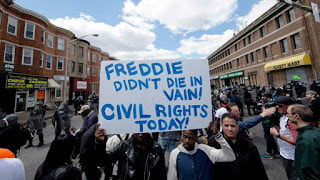

CEOs are consequential people. They have a central role in organizing the firm, choosing subordinates, and proposing strategies to their boards and implementing them. We know that (most) CEOs have ideologies and personalities. We don’t know much about how these two interact to shape what firms do. Until now. Let’s start with a simple fact: a CEO can be anywhere from liberal to conservative in political ideology and can be either low or high on narcissism (self-grandeur and self-indulgence) and extraversion (communication need and ability). So there are narcissist liberals and extravert conservatives, and the other way around, and liberals and conservatives who are neither narcissists nor extraverts. Does this matter? New research by Abhinav Gupta, Sucheta Nadkarni, and Misha Mariam published in Administrative Science Quarterly shows it does. Their idea was that CEOs’ narcissism and extraversion could make their companies act more ideologically. Narcissists think that their view of the world is the right one, and extraverts are good at persuading others. In both cases the result is that the firm becomes more ideological. (A firm doesn’t have to be liberal or conservative, of course, and would be ideologically neutral if its CEO were neutral.) So what did the evidence show? Downsizing the firm is a typically conservative action and was in fact more often done by conservative CEOs – especially if they were extraverted. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a typically liberal action and was more often done by liberal CEOs – especially if they were narcissistic or extraverted. There was one non-finding in the study’s interactions: narcissism does not make conservative CEOs downsize their firms more. There are many possible explanations, one of which is that narcissists think of themselves and everything associated with them as being grand and great. Shrinking the firm likely isn’t their first choice of action, even if there are good reasons to do so. Clearly ideology and CEOs’ personalities shape firms. They do so in ways that can make CEOs pretty scary, given the mix of ideology and personality that one can find. CSR is a good thing for society, but if it is done by a narcissistic liberal CEO one has to wonder whether the firm’s resources are used well. Downsizing can be necessary, but if done by an extroverted conservative CEO one has to wonder whether others thought differently but were persuaded to reduce the firm’s employment more than they should. Both are scary thoughts. The article can be downloaded for free for a limited time: Gupta, A., S. Nadkarni, and M. Mariam 2018. "Dispositional Sources of Managerial Discretion: CEO Ideology, CEO Personality, and Firm Strategies." Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  I just saw research on how to successfully start a new venture that made me think about the Wimbledon tennis tournament. Here’s why: some of the things that are obvious sources of strength in tennis are widely thought to be weaknesses in business – but if current research is any guide, they are strengths. Concentration, vision, and practice through endless repetition are how champions are built in tennis, a sport where the average serve speed is 180 km/h for men and 155 km/h for women. But how is that related to new ventures? Research recently published in Administrative Science Quarterly by Susan Cohen, Christopher Bingham, and Benjamin Hallen looks at how new ventures perform in accelerators, which are training and development programs for new ventures. They looked at many accelerators to find out exactly what activities accelerate and improve a venture more, because some accelerators have been successful in helping launch new ventures but others have not. Before they started, we knew very little. Their findings were clear – and completely the opposite of some common beliefs about forming and improving new ventures. Belief 1: New ventures should start with a solid business plan and be given information and introductions to potential mentors gradually over time to develop their ventures. This is not true. Ventures should be given concentrated consultation and advice early in the founding, because that is when the value of new information is highest. The venture may be most flexible and uncommitted at this stage, but even if it isn’t, Cohen, Bingham, and Hallen found that the concentration of feedback was key: it helped venture founders overcome their own biases and assumptions, connect with potential customers, rethink what would be best for the business, and act on the new information. Belief 2: Entrepreneurs should avoid divulging information about their activities to other entrepreneurs, who might steal their ideas. This is not true. Yes, we’ve all learned since childhood that secrets are valuable, but in business, quality trumps secrecy. New ventures in accelerators were able to understand their own business much better and improve faster when they had a clear vision of what other ventures were doing. That was only possible when they also shared information about their activities. Belief 3: New ventures should have development plans customized to their needs. This is not true. The problems faced by new ventures are very similar, so using a standard process that lets ventures practice how to overcome these problems is best. New venture founders don’t know what they don’t know, so by customizing – seeking input and knowledge from only the people they assume will be most useful to them – they create blind spots. How can we be so wrong about the factors that create successful new ventures? All venture founders, advisors, financiers, and researchers have incomplete information and bounded rationality. Ventures are typically not visible until they have reached a certain size and become full organizations, so there is not enough knowledge about the crucial founding phase. And we humans learn from what we see in very limited ways, strongly shaped by prior beliefs and selective use of examples. The secrecy belief is a good example, because it is such an old myth that people rarely challenge it. The best accelerators go against these three beliefs and foster concentration, vision, and practice. Their ventures are much more successful than those of accelerators that follow the conventional beliefs. Entrepreneurs should take note, even if they are not part of an accelerator. I think Serena Williams would approve. Cohen,Susan L., ChristopherB. Bingham, and Benjamin L. Hallen. 2018. The Role of Accelerator Designs in Mitigating Bounded Rationality in New Ventures. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  In many areas of life, we enjoy competition. Right now, there is lots of excitement in Wimbledon. There is even more in the World Cup, where entire nations seem to believe that they are in matches with each other – not 22 selected players, most of whom play professional football outside their home country. The excitement extends to management practices too, where various prizes and rewards are distributed along with pay adjustments, all as a function of how well each employee is thought to perform compared with others. “Competition cures laziness,” is the belief. What could possibly go wrong? The answer is found in a paper by Henning Piezunka, Wonjae Lee, Richard Haynes, and Matthew Bothner in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. They look at Formula 1 racing, which is a place where one can find drivers who enjoy competing and are used to competing. After all, who would drive a car at such crazy speeds very close to other cars if they didn’t think competition was a great thing to do? But even in Formula 1, there are costs to competing. The cost is a simple and important one: close competitors collide more often. In F1 driving, colliding is never a good thing: minor collisions damage the cars and slow them down, intermediate ones make cars useless, major ones kill drivers. Yet collisions occur, and it turns out that they happen more often between drivers with similar accomplishments during the season. That’s interesting because it means that the most perilous situation is when two people are near each other in two ways – similar social status, and capable of giving each other trouble. But wait, it gets worse. The intensified competition is seen even more clearly if the drivers are also similar in other ways. Similar-age drivers collide especially often if they have similar status. The same is true when the stakes are high, such as when the drivers are high in the tournament ranks and the season end is drawing near. These conditions sound a lot like those facing employees in firms that motivate by tournament. This gives a good account of when we can expect F1 drivers to collide, but it also means more. Many of the modern ideas of management and motivation rely on the idea that tournaments are good and should be encouraged through various rewards and prizes. They don’t take into account the conflict that results. If they did, would these practices still be as popular as they are now? Piezunka,H., Lee, W., Haynes, R., & Bothner, M. S. 2018. Escalation of competition into conflict in competitive networks of Formula One drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.  Misunderstandings are common in the workplace. An important one is between customers who are confident they know how employees are supposed to do their jobs and the employees who are equally confident that the customers are clueless. Sometimes this is amusing, as when patients go to a doctor convinced that they will get exactly the medical leave and medicine they have in mind. Sometimes this has serious consequences, as when those in public service occupations like the police see the general public as ignorant, hard to control, and potentially dangerous, and resort to using tactics that are effective but harmful. Two natural questions are how to improve understanding and what happens when understanding is poor. A recent article in Administrative Science Quarterly by Shefali Patil looks at the second of these questions and finds surprising effects of police officers’ political ideology on what happens when they feel misunderstood by the public. We might expect that feeling misunderstood would lead to a decline in performance, but that is not true for all officers – it is true only for liberal-leaning police officers. Conservative-leaning police function the same whether they feel more or less understood – they seem immune to any ill effects of feeling misunderstood. What is going on? Patil points out that community understanding is an important part of liberal ideology: liberal officers expect the public to understand them. When that understanding is missing, the liberal police officer experiences doubt about the social order and about the best way to interact with the public to promote community understanding. Conservative ideology is different because it celebrates authority, and an important part of belief in authority is that those holding authority do not need to be understood by others. Not being understood means having less information, but it also reinforces the beliefs of a conservative police officer about how best to interact with the public in doing their job. The effects of ideology run even deeper than this. Further study of the extent to which police officers felt they were understood by the public showed that this, too, was split along ideological lines. Conservative officers were more likely than liberal officers to believe that the public did not understand them. The picture painted by these studies is one of police officers shaping their understanding of the world, including whether the public understands their work, according to their political ideology. They then interact according to this belief, and if they believe that the public does not understand them and does not need to, as conservative officers do, they can function well even when public understanding is low. Facing the same circumstances, liberal officers tend to be more uncertain in their actions and perform less effectively. You might think this is not a problem, because the findings seem to show that everything is well as long as officers’ political ideology aligns with public understanding. But things are not that simple. There have been cases of suspects dying in police custody because of the way they were restrained, and many of these involved the suspect or bystanders warning the police that their actions were dangerous. A police officer who believes that the public understands will listen to such warnings; one who does not will see them as misinformed and will ignore them. Ideology matching beliefs of public understanding may work well much of the time, but sometimes it has tragic consequences. Patil, S. V. 2018. “The Public Doesn’t Understand”: The Self-reinforcing Interplay of Image Discrepancies and Political Ideologies in Law Enforcement. Administrative Science Quarterly: forthcoming. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed