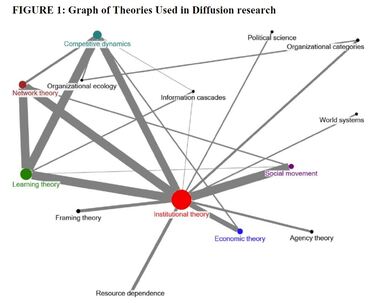

We are well aware of the advantages of knowledge, both when doing something conventional and when making innovations. People who teach entrepreneurship do it because knowledge helps the foundation of a successful venture. But is there such a thing as too much knowledge? When I work alone, more knowledge is better – it generally gives performance at a higher level, and it gives the creativity that can yield outstanding outcomes. My earlier researchon innovations in the comic book industry is one of many research projects showing this effect. Things get more complicated when multiple people come together to do something complex like founding a new venture. The great benefit of having much knowledge and many kinds of knowledge is the potential for combinations that others cannot think of. The problem with doing this in a team is that combining knowledge requires communication, and communication gets harder when each member has different types of knowledge. So how to resolve this dilemma? Research by Florence Honoré published in Academy of Management Journal shows a nice path. The idea is simple: variety in knowledge is great as long as it stays within one person, but teams should also have shared knowledge that transfers directly to the problem they are solving. This makes sense if we think of specialized knowledge as roughly equivalent to languages. People with shared experience speak the same language, while people who have different experiences need to translate. A person with many kinds of knowledge is a polyglot, and that is OK because we are all good at talking to ourselves. So what did the research show? New ventures were at great risk of failing if their venture team had a mixture of experiences across team members, and this problem got worse the more founders had earlier been employed by multiple firms. On the other hand, more shared experience among the founders helped the firms survive, and this was especially true if the venture had multiple founders who transitioned from the same prior employer to founding a venture together. The implication for entrepreneurship is obvious. A team with experience in the same industry that they are forming a venture in will perform better, and they will do especially well if they make sure to also have one member with a variety of experiences. And, they should listen carefully to that person, because it is exactly the integration of knowledge from this polyglot member that can benefit the venture most. In other words, this research is another win for diversity in business. Honoré, Florence. 2021. "Joining Forces: How Can Founding Members’ Prior Experience Variety and Shared Experience Increase Startup Survival?" Academy of Management Journal forthcoming.  A new book will be published soon, “Strategic Management: State of the Field and Its Future,” edited by the excellent scholars Irene Duhaime, Michael Hitt, and Marjorie Lyles. My chapter is titled “The organizational view of strategic management,” and it synthesizes how the fields of organization theory and strategic management have moved towards each other already and will probably continue to do so in the future. Why is this, and why does it matter? Let us start with the second question. There are two widespread myths among students of strategy, including researchers, and executives also believe them. The first is about the power of the individual decision maker. This myth almost makes sense. All of us make decisions many times a day, starting with simple stuff like choosing goods to buy and moving up to life-changing decisions such as educational choices. We feel powerful when doing that. But are we independent? Maybe we think we are, but do you really think that the enormous sums spent on marketing to influence our decisions are wasted? Research says they are not. We make decisions, but not independently. Executives making decisions feel powerful too, only more so. And why not, executives making strategic decisions can allocate and redirect enormous sums of money and hours of effort. But are the executives independent? It does not take a large organization to make the executive completely dependent on information about the internal organization and external environment that is captured, processed, and presented to the executive by others. The individual choosing a cereal is influenced by marketing. The executive making strategic decisions is a product of the organization. The second myth is that strategic decisions are a simple matter of picking the option that maximizes the economic value of the firm. If only that were true: life would be easier and we could pay executives much less because it is not hard to line choices up by value and pick the best. But strategic decisions are about uncertainty and evolution. They reach into the future, so the alternatives cannot be lined up by value, but it is possible to understand the type and size of uncertainty, and it is also possible to make choices that alter the uncertainty. They reach into the future, so it is important to guess how the world changes, and how the organization can evolve to match the world, or even influence it. The solution to these two myths is to view the organization as the strategist. The responsibility for being strategic does not really lie with specific executives like the CEO, it is spread throughout the organization as its divisions, functions, teams, and individuals deal with a changing world, seeking to adapt to it and communicate what they have learnt to each other. It is in this interface that the fields of organization theory and strategic management communicate with each other. Strategies are shaped by societal groups outside the organization, individuals and groups inside it, the commitment and learning resulting from past strategies, and the goals formulated to manage past strategies. All of this is organizational, and all of it is strategic. Despite these overlaps, organization theory and strategic management do not always communicate well. Organizations do not determine strategies, but some researchers think they do. Strategies cannot be chosen independent of organizations, but some researchers think they can. The reality is that organizations are stuck in an adaptive strategic cycle. The modern synthesis of organization theory and strategy is that problem and opportunity discovery by internal decision makers directs strategic change, and this strategic change in turn modifies the organization over time. More and more researchers in organization theory and strategy do their work with this adaptive cycle in mind, and in doing so they advance both fields of research. And this research in turn improves the teaching of management, and the practice of management.  Is it possible to copy what others do and still become different from them? That seems like a paradox, but it could be reality in the world of organizations. Here is how it happens: Some new practice appears that claims to solve a problem, for example a technological innovation or a management technique. Is the claim true? It might be, but it might not, and the uncertainty about the value of an innovation is a problem that management needs to solve. Often, looking at what others do and copying them is an easy and smart solution. But if that is what organizations do, they should become similar to each other, right? Wrong. Organizations are multidimensional in their activities and the environments they face. Some organizations copying others does not mean that all organizations do; they are often trying to solve different problems. Some organization copying specific other organizations does not mean that all organizations do; they often have different peer reference groups. Some organizations copying other organizations does not mean that they fully accept what the others do as true; they often try out innovations and reject those that do not fit their needs. For each new practice all these processes occur, and organizations live in a chaotic environment with many new practices that spread and are copied. What we see is the diffusion of differences. How do we know this? In a recent research paper published in the Academy of Management Annals, Ivana Naumovska, Vibha Gaba, and I checked the last 20 years of diffusion research – 178 research articles in total. What did we find? First, less than half the studies reported how many organizations adopted a practice at the end of the study period, but from the studies that did report, less than 20 percent adopters was the most common result. Why did organizations react so differently? Usually because they faced different environments, so they were solving different problems, though other differences such as past learning and network ties also distinguished adopters from non-adopters. Looking over the past research, the diffusion of differences is a consistent finding across the articles. This brings me to the second paradox. Most diffusion researchers believe that diffusion leads to similarity, or in their language, “mimetic isomorphism.” Why? One reason is that the diffusion of differences is surprising conceptually. It is hard to believe until you examine the evidence and think about the process. The more important reason is that the researchers have started with a deservedly famous theory article, “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizations Field” by Paul DiMaggio and Woody Powell, and have gone on to over-interpret its conclusions. In that paper, copying other organizations was one process that could lead to similarity. Researchers these days say that copying other is a process that does lead to similarity. These are very different claims. Our conclusion? First, obviously, theory should not get in the way of evidence. Second, the strong belief in diffusion creating similarity means that there are lots of holes in our knowledge about what diffusion processes do. Because differences among organizations have been overlooked, we simply do not know enough about their sources. Naumovska, Ivana, Vibha Gaba, and Henrich R. Greve. 2021. "The diffusion of differences: A review and reorientation of 20 years of diffusion research." Academy of Management Annals forthcoming. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed