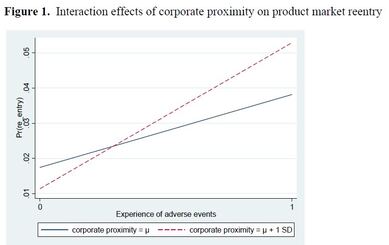

Did you know that companies are full of would-be heroes? They are the managers of subunits, units, functions, and any other subdivisions of the company. They are doing their jobs, keeping their units efficient and fulfilling their goals, but what they really want is a crisis of some sort—a crisis that brings out their true potential as heroes who can make the necessary changes, right the course of the units they are managing, and prove that they should be promoted to greater responsibility. We like heroes. Companies promote heroes. But few ask the question of whether there are situations in which a hero creates loss for their company, even as they are trying to win by overcoming a crisis. Recent research by Julien Clement published in Administrative Science Quarterly looks at this question and finds some worrying answers. The context for drawing these insights is interesting, by the way, and explains the choice of hero in the illustration. He studies teams in the online game DOTA 2, which experienced multiple challenges due to rule changes. The start of the insights drawn from the research is that organizations are coordinated systems, so any attempt to change one unit can have consequences for other units. Change in one place usually makes the entire system a little worse, until corresponding changes are made elsewhere. When heroes do their work, they also put other heroes to work. That is only the start of the insights, though, and the continuation is worse. It is important to also ask why a crisis happens. Maybe it is because the hero’s particular unit experiences a local problem, for example related to the technology it operates, the inputs it gets, or the market for its outputs. But it could also be because of a system-wide problem that affects the entire company. If that happens, problems will occur in multiple units at once, and the changes to each unit will affect other units, creating a very confusing environment where it is hard to tell the difference between the original crisis and the new problems created by other units’ changes. When heroes go to work on the same problem and don’t coordinate, the problem can grow bigger. If heroes might lose, then what is the alternative? Simple. Any organization has a center, and when the entire organization is hit by a system-wide problem, the center needs to take charge. This is the time for a CEO and top management team to diagnose the system-wide problem and search for a solution. The system needs to change. Of course, the heroes can still be given work, but the task of each one should be defined and distributed centrally. (Notice how this explains why the Marvel heroes always struggle unreasonably much given their abilities – they are not centrally coordinated, but their adversary is.) The lesson for an organization is clear. The idea of operating it as an independent adaptive system is wonderful for the sequence of small and local challenges that constitute its daily life. At the same time, it is exactly the wrong approach for dealing with larger, system-wide problems that occasionally happen and sometimes spell the difference between success and failure. Clement, Julien. 2022. Missing the Forest for the Trees: Modular Search and Systemic Inertia as a Response to Environmental Change. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Should we care about how firms use colors? That sounds like an unusual question, and I will soon give an even more unusual reason we now know something about the topic. Let me first suggest a reason to care, though: firms appear to be pretty conscious of color choices in logos. We may suspect that they rely on outside consultants and imitation quite a bit in selecting colors, of course. Notice how many web platforms and other IT firms seem to have a liking for various shades of blue (Microsoft Edge, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn) or have remarkably similar “rainbow” logos (Microsoft, Google, old Apple). So, they seem to care, but it is not clear that they think very independently about their color choices. How does that observation match our knowledge of color choices? Truth is, we know very little, but recent research by Stoyan V. Sgourev, Erik Aadland, and Giovanni Formilan published in Administrative Science Quarterly gives an interesting start. This research was not about Facebook, though, or any kind of firm: it was about the album covers of Norwegian black metal bands. This sounds somewhat unrelated to how firms choose colors, but if you stay with me a bit, we may be able to make a connection. The researchers showed that indeed color matters a lot for positioning, and in two ways. The first is that color is chosen with respect to peers. To position themselves initially, the black metal bands’ album covers primarily featured black (obviously) and other very dark or muted colors, and these color choices were influenced by peers’ choices. The second is that color is chosen with respect to the environment. Black metal bands were for a while under attack societally because of non-music activities such as church arson. Interestingly, their album cover design choices became less black during this time period, which made sense given a wish to dissociate themselves from news stories about crime and associated stigmatization. Although most firms are very different from black metal bands, we can suggest some connections. Colors do seem to indicate similarity with peers or competitors, so early choices of color by a group of similar firms or an industry probably matter a great deal. Color is also seen as symbolic, at least implicitly, and firms will pay attention to this symbolism. Exactly what symbolism is influencing the choice of blues by web platforms and other IT firms is not entirely clear to me, but blue does give an impression of cleanliness. (So does white, but white is not a practical color to use as a firm symbol on a computer screen.) We should also keep in mind that firms can be more strategic in color choices than the copying of color that we see so often. I mentioned that Apple, in its early years, had a rainbow logo similar to the logos currently used by Microsoft and Google. Its current color choice is different: Apple has been black, and it is currently grey. What does that mean? Interestingly, grey is also a color that gives a clean image, though it is arguably cooler than blue. It is also distinctive from the logos used by other firms with similar products and services. For Apple, that could be exactly the point: they have found one more feature shared by firms in the industry that Apple can use to show how unique they are. We still know little about colors. What we do know suggests that firms care about colors, but they tend to mimic each other. Mimicry does not indicate the most conscious of choices, but as Apple shows, it is possible to make independent choices that can be distinctive and smart. That is worth thinking about. Sgourev, Stoyan V. , Erik Aadland, and Giovanni Formilan. 2022. Relations in Aesthetic Space: How Color Enables Market Positioning. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Our economy and society are currently seeing a big change. Many firms are replacing the traditional management practices of supervision, goals, and managed rewards with a market turn that exposes workers to the risks and rewards of competitive markets. This is seen in many places, from the “contractors” delivering meals or transportation services under app platforms all the way up to investment bankers taking a cut from each deal. Do we know what this does to people? We do not, which is why research like Alexandra Michel’s recent publication in Administrative Science Quarterly is important. She looked at bankers’ transition into market-exposed roles, which usually happens after 9 years of employment. What she found was remarkable, because it demonstrated that moving from managed rewards to market rewards is a radical change that alters the mind and body of the worker. Why is that? Think about what life is like for most workers in regular organizations. Their role is defined, their goals are defined, and the work is structured by supervisors or pre-defined organizational processes. It is a predictable life. If they have contingent rewards or incentives, the goals to fulfill have been specified in advance and the resources to reach the goals are in place. At most, things could be unpredictable because managers rank workers, so the rewards to one depend on the others. Still, this is a pretty predictable life. Market-exposed work is different. The role is to meet demand in whatever form the demand takes. The Uber driver (for example) needs to be in the right place at the right time. The investment banker needs to bring the parties of a potential deal together, so they agree on the terms. This is an unpredictable life. Effort and rewards are no longer connected as well because the market is unpredictable, and there is little reward outside that given by meeting demand. And strangely enough, although highly contingent rewards in conventional organizations make people work hard, the market turn makes people work harder simply because there is always one more potential, but uncertain, reward that seems to be within reach. The result is overwork. And more importantly, unlike the managed employees, the market-exposed employees mostly blame themselves. After all, they are entrepreneur-like in job description and should be designing work so that they actually meet market demand. Business failure is personal failure, both in their mind and in those of their colleagues, who subscribe to the same belief system. The solution is obvious. They need to manage their body and their mind in order to be strong enough for the overwork and stress of their role. And this is where it gets scary. The bankers Michel studied read about medical drugs of various kinds and made liberal use of doctors who would give them the medications they asked for. Some of them even found foreign mail-order suppliers of drugs that would enhance the performance of the mind, or conceal fatigue, or handle various medical breakdowns. Because body failure meant business failure, they manipulated their bodies. Incentives are supposed to be good for organizations, and market incentives especially so because they allow worker and organization to completely agree on what should be done. Only now are we beginning to understand that they can also be exceptionally harmful for the worker. Michel, Alexandra. 2022. Embodying the Market: The Emergence of the Body Entrepreneur. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  We all try to learn from our failures, and we believe that we usually do so successfully. Similarly, we often think that firms can learn from failures, and this belief is shared by people who observe (and work in) firms and those who study organizational learning. It may be shocking to realize that some of the details on whether and how firms learn are not well documented. For example, we know that firms will change something after experiencing failure, but we are rarely able to measure whether they change the right thing and whether the change is an improvement. This is why research by Cheon Mok (John)Kim, Colleen M Cunningham, and John Joseph published in Academy of Management Journal is interesting. They checked whether medical device firms could distinguish between failures caused by product features or market conditions and found that they could. So far so good. They also checked whether failures due to product features led to re-entry with a new product, and this is where things got more complicated – and interesting. The answer is yes, but not always. More importantly, the researchers could distinguish the conditions that made such learning more likely. If the business unit that withdrew a failed product was close to the corporate headquarters – geographically, in the organizational hierarchy, or in product lineup – then it was more likely to re-enter with a new product. What is so distinctive about being close to the corporate center? One feature is attention and surveillance; another is support and resources. These seem like heads and tails of a coin, and clearly either one could have this effect, and most likely they act in concert. In fact, the findings were even stronger for the more repairable types of failures. If the failure was distinctly from the product design, not the user, then corporate proximity had greater effect. If the product failure was severe, then corporate proximity had greater effect. In both cases, the fault is more obvious and more easily traced to the firm, and accordingly it should be easier to learn from failure. And learn they did. This is important knowledge for two reasons. First, although we often assume that learning from failure happens, it is often the case that the very things we assume to be true are faulty in some way, and need to be checked carefully. That is also true about learning from failure, because the conditions that make it happen are not always present. The firm with highly decentralized management that is also geographically dispersed and diversified has three strikes against learning from failure. There are many such firms. This brings us to the second point. From what we know about learning, we should also be able to design organizations that learn well. Given how learning is related to connections within the firm, and the attention (and surveillance, support, and resources) that follows, designing firms with structures that fail to learn is a completely unnecessary error, especially given the costs of simply giving up when re-entry with an improved product would have been possible. If we know how firms learn, we can design them to learn well. Kim, Cheon Mok (John), Colleen M Cunningham,and John Joseph. 2022. Corporate Proximity and Product Market Reentry: The Role of Corporate Headquarters in Business Unit Response to Product Failure. Academyof Management Journal, forthcoming. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed