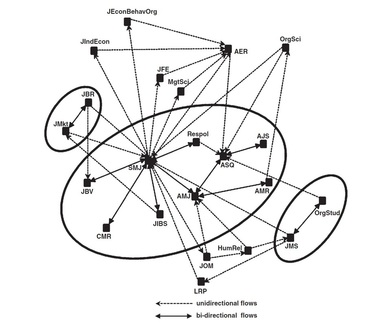

Research and news tell the same story: there is discrimination both in employment and in business. Women are few and far between among executives and founders of technology firms, and claims of bias are often made, especially in Silicon Valley. On the financing side, venture capital firms appear to disadvantage women in executive roles. #AirbnbWhileBlack is hashtag collecting discussions of discrimination, and has led to Airbnb examining its processes for retaining hosts. This looks like a problem for women seeking to start businesses, especially if those businesses are in industries with few women to begin with, like high technology. Even worse, the tendency to favor similar people to oneself – homophily – could make this even worse. Interestingly, a recent article in Administrative Science Quarterly by Jason Greenberg and Ethan Mollick has found a counter effect. The idea is that if a minority thinks that it is discriminated against, it will be especially supportive of its own members. It will not only favor its own, as all groups do, but it will do so in an activist way. If this happens, being recognized as a disadvantaged minority – like women in technology – will lead to better treatment, at least from members of the same minority. Does it happen? It is not clear whether this is always true, but one good place to look is in crowdfunding, where ventures and their founders are presented to a “crowd” of any interested funder, and they in turn decide what ventures to back. And indeed, women Greenberg and Mollick found that women targeted women’s ventures for funding, and did so especially for industries were women are known to be scarce. So, women especially supported other women not fashion or publishing, where women are frequent business founders, but technology, where they are scarce. This is clearly not a reason to think that discrimination will balance out. Crowdfunding is the form of funding where this type of activist support is most effective, but most venture funding is not down through crowds – and we already know that venture capital firms, for example, have mostly male executives. Also, activist funding does not have large effects when there are few women funders to begin with. So, we can conclude that this provides some relief, but it is a less fair solution than simply evaluating ventures on their merit. Greenberg, Jason and Ethan Mollick. 2016. "Activist Choice Homophily and the Crowdfunding of Female Founders." Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Organizations can have very different work environments, including differences in the respect they give to employees. Organizational cultures differ, and managers differ, in whether they see employees and valuable and how well they acknowledge this. Many organizations think that it makes a difference – notice how I used the word “employee” just now, but actually words like “colleague” and “team members” are frequent in actual work. Does this matter? For an example of how much this can matter – in a very special context – a recent paper in Administrative Science Quarterly by Kristie Rogers, Kevin Corley, and Blake Ashforth looked at an organization that operates professional call centers as part-time work for selected inmates in prisons. Every day inmates go to work in their orange jump suits (yes, just like in the TV series). Every day they go back to the prison wing after working. But this work is not like the demeaning chain gangs that we see in some old movies; the organization (Televerde) values its inmate workers and gives them both encouragement and respect. So what happens? The respect they get from their Televerde managers, and from customers, changes lives. They get a specialized respect based on the value of the work they do, and their performance, and this gives excitement and self-respect. They get general respect from being seen as real people with lives and accomplishments, not inmates with orange jumpsuits and numbers, and this gives ideas of a changed and improved life. Together, these two kinds of respect, and especially the general one, puts the inmate-workers on a path toward removing themselves from their identities as current and future inmates, and attaching themselves to a new identity as a professional doing legal and respected work out of prison. It happens impressively fast. These changes were easy to see over a period of less than a year (for most it was much faster), even though the Televerde workers were still in the prison wing, with their old friends and controlling prison wardens, every day after work. As part of the identity journey, they needed to transition from their old thinking habits – the orange in their heads – to a new way of seeing themselves as part of a regular civil society that they could not yet reach because it was outside the prison walls. Remarkably, they were able to not just see their inmate identity and their worker identity as separate beings coexisting in their minds, they also could shift to a new and holistic identity that would guide their lives after they were released from prison. Giving workers respect is seen as important also in regular organizations, with no inmate workers, but there is a certain degree of cynicism about its effect, and there are also managers who don’t think it matters. After seeing how transformative it can be under these conditions, when it is done honestly, maybe it is time to reconsider. Rogers, Kristie M., Kevin G. Corley, and Blake E. Ashforth. 2016. "Seeing More than Orange: Organizational Respect and Positive Identity Transformation in a Prison Context." Administrative Science Quarterly.  So the US election ended with a Trump win, and the stock markets plunged in response – especially Wall Street. Then, less than a week after, stock prices rushed back up. What happened? Let’s start with the simple observation that we were observing stock sales and buys by investors, who sell and buy for profit, and who have a lot of experience selling and buying. These wild movements were not a result of ignorance, and not a result of playfulness either. Investors chasing value drove prices down and back up, and lost and gained money. And, this was not a unique event, we are familiar with dramatic price changes as the market responds to uncertainty. What drove these events was in fact a fundamental process that has been studied long, and we can go back to a paper by Hayagreeva Rao, Gerald Davis, and myself in Administrative Science Quarterly in 2001 to learn about it. People making decisions under uncertainty try to learn ways to reduce uncertainty. When they are looking for value, one way is to learn from others. After all, if we see someone moving toward one option, or away from it, their decisiveness could indicate that they know something that we don’t know. But people can be decisive for many reasons. They may have correct knowledge. They may have incorrect knowledge. They may be impatient. But learning from others can be very tricky when those others act on incorrect knowledge or impatience. This was known before our study. What we found went one step further. Learning from others is especially tricky when those others learn from others. In that case, it is enough for some people to make decisions without correct knowledge. Others do the same learning from them, and then others do the same learning from those who learnt from them. And so on. See how this can make stock markets plunge, with very little basis in fact? Or increase? In fact, our research was based on stock market actors – not investors, but stock analysts. They want to cover firms that are good but overlooked, because analysts are most useful for investors if they give scarce information on valuable opportunities. But we found that when analysts were chasing valuable firms, they were in fact only chasing other analysts. And the later they were in learning from others, the less valuable were the firms they found. This is a problem that extends much further than stock markets, though it is easier to prove there than elsewhere. Learning from others is a good strategy as long as it is not over-used. But, those who learn from others typically don’t stop using that strategy soon enough, so at some point it becomes costly. Again and again we see people, and firms, chasing fool’s gold: opportunities that looked good to the first who entered, but only because of incorrect information. Rao, H., Greve, H. R., & Davis, G. F. 2001. Fool's gold: Social proof in the initiation and abandonment of coverage by Wall Street analysts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46: 502-526.  Administrative Science Quarterly is a generalist journal covering a wide range of research on organizations, as you can see in its invitation to contributors. One might think this would make it less influential in any particular topic, but this is not true. The leading generalist journals are seen as more prestigious than specialized journals, and as a result they get top quality papers, especially if those papers are meant to have wide impact. This gives them more readers, and readers who pay more attention. Equally important, generalist journals are places that assemble papers with multiple ideas that can cross-fertilize fields of study. Often they are the places to look for ideas that will grow and rejuvenate fields. So is that true for ASQ and strategy? A paper by Sridhar Nerur, Abdul Rasheed, and Alankrita Pandey looks at how strategy developed over time, focusing on research in Strategic Management Journal and journals that cited it, or were cited by it. This inflates the influence of SMJ a bit, but is fair enough because SMJ is the leading specialist strategy journal. Next they looked at citations between journals staggered in time periods. These changed over time, as strategy research took shape, but I think that the figure below is a good example because it shows 1995-1999, which was a time period in which the strategy field nearly had its current shape. Notice that there are two-way arrows between the leading generalist journals ASQ and AMJ (Academy of Management Journal), and ASQ and ASR (American Sociological Review). Other than that, all the arrows show journals learning more from ASQ than ASQ learns from them – they are one-way arrows (the arrows point in the direction of citations, so an arrow into a journal means a citation to the journal, which is the same as acknowledging influence from the journal – confusing, I know, but important). Interestingly, in this time period, there is no direct influence from ASQ to SMJ, so we cannot see ASQ shaping strategy directly, but we can track indirect influences such as ASQ to ResPol (Research Policy) to SMJ. This pattern of indirect influence started in 1990; before that ASQ directly influenced strategy. Does this mean that ASQ was a starting point that lost influence? Not at all. In fact, all these journals cite each other, so the graph just shows the highest-volume citation paths. When adding up the paths, the total influence can be found, and Nerur, Rasheed, and Pandey show that ASQ maintained a top 3 rank as a source of new strategy knowledge in all time periods except 1985-1989. They also show a broader point—in the top 5 most influential journals in strategy, only one was a specialist: SMJ. So we know that ASQ is influential in strategy, but it is not a strategy journal. It is a prestigious generalist journal, which makes it influential in many fields. Nerur, S., Rasheed, A. A., & Pandey, A. 2016. Citation footprints on the sands of time: An analysis of idea migrations in strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 37(6): 1065-1084. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed