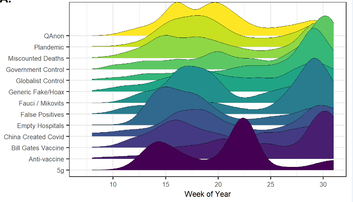

I am sure you have read the news about how a variety of COVID-19 conspiracy theories have persuaded many people that the pandemic is a fake and manipulative scam, possibly involving a disease no more harmless than flu. Or the ones saying it is a deadly attack weapon designed by some secretive perpetrator. Maybe you have also thought about how this is a modern phenomenon, driven by domestic and foreign manipulators exploiting the easy access to social media. And surely you have felt sorry for the people who believed that Covid was harmless and ended up sick because they failed to protect themselves. But this story is only half true. The pandemic is new and the specific conspiracy theories are new, but conspiracy theories of various kinds are a permanent feature of our society. People share variations of them in face-to-face conversations, in writing, and now also on social media. Who are these people spreading conspiracy theories? Why do they do it? In research published in American Sociological Review, these issues are explored by Hayagreeva Rao, Paul Vicinanza, Echo Zhou,and me. Conspiracy theories make threats more understandable, and thereby give a feeling of mastery and control. This may seem ironic because conspiracy theories always involve some hidden plot by secretive perpetrators. That’s exactly the point though. The conspiracy theorist is the one who can see through the concealment and understand the plot. And sometimes the plot means that the apparent danger is not real (the scam disease). Even when the danger is real (the disease as weapon), some people will find the thought of a human attacker more comfortable than that of a mindless virus feeding on people to reproduce itself. How do we know that conspiracy theories help people cope with the pandemic threat? Simple. One of the drivers of social media Covid conspiracy talk was the infection rate. More infection, more conspiracy theory talk. Conspiracy theories counter threat and reduce fear. Conspiracy theories have moderate and extreme versions. This is easy to tell by looking at their content. The “film your hospital” conspiracy theory was about hospitals pretending to be filled with patients (for money, or for political reasons). This is moderate. An example extreme version is Bill Gates orchestrating the pandemic for various evil purposes. Another is Covid being a way of controlling people while constructing malicious 5G towers. Why does it matter that the conspiracy theories differ in how extreme they are? Simple, again. One of the drivers of social media Covid conspiracy talk is that the moderate versions are gateways that get people into conspiracy talk. Later many of them graduate to extreme versions. Conspiracy theorists can spread different conspiracy theories, often at the same time. And remarkably, often conspiracy theories that contradict each other. Logically, Covid can’t both be a harmless scam and a deadly weapon, but the same people would spread both within the span of a week (and yes, these were people, not bots – we can identify bots). How to make sense of this? Maybe the best way to sum it up is that conspiracy theories are a form of reality denial. When the reality is threatening and difficult to explain and rationalize, as it is during a pandemic, a conspiracy theory offers an escape. But the escape is not perfect, because our society is full of people who don’t believe in conspiracy theories and will challenge the believers. That’s why some poeple have multiple conspiracy theories. Whenever one of them is challenged, the conspiracy theorist can fall back on another. What to do about such reality denial? The starting point must be that it is not simple ignorance. Reality denial is motivated reasoning, and facts alone will not help. Explain how one conspiracy theorist is false, and the conspiracy theorist will fall back on another. Because it is motivated by a wish to reduce and control threat, the solution always involves explanation of how the threat can be reduced through human action. It is a difficult conversation because masks, isolation, and vaccinations all have this effect, but conspiracy talk does not go away unless we explain how the threat can be reduced through joint action such as vaccinations and personal caution. Greve, H. R., Rao, H., Vicinanza, P., & Zhou, E. Y. (2022). Online Conspiracy Groups: Micro-Bloggers, Bots, and Coronavirus Conspiracy Talk on Twitter. American Sociological Review, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224221125937  In the ideal world, we would like firms to make a profit and also to help the environment and society. Indeed, the turn toward ESG (environment, social, and governance) evaluation of firms is evidence that this is important to many, including a growing niche of investors who favor firms that are responsible as well as profitable. Are we living in this ideal world already? Or if not, are we moving toward it? The answers are not clear. In a recent article in Administrative Science Quarterly, Ben W. Lewis and W. Chad Carlos looked at how firms reacted to being rated as charitable. Being rated as charitable is supposed to be good, both because it means that they contribute to the social dimension (the S of ESG) and also, indirectly, that they are profitable enough that they can afford to do so. Many firms cannot. If we lived in the ideal world combining profits and ESG, or even a more limited world combining profits and social contribution, managers would savor such a rating and continue making philanthropic contributions. But in fact, firms rated as charitable reduced their philanthropic contributions. How can this be? To begin with, we can dismiss the idea that firms don’t care about ratings, because there is much evidence that they care and that they try to get high rating outcomes even it is costly to do so. If high ratings matter and executives decide to avoid a high rating outcome, something else is at work. The explanation has two parts: competing logics and reactivity. Competing logics exist when firms are rated – or more broadly, evaluated – on multiple criteria, and these are backed by different groups with conflicting interests. For firms, the main group that executives worry about are shareholders, of course, and their interest in maintaining steady profits and investments in gaining future profits. The logic in this is how firms can accomplish the valuation increases and dividends shareholders crave. Through this logic, money given away to philanthropic contributions is just like money invested to protect the environment that does not also increase productivity. It not only reduces current valuation increases but may also hold back investments that would help future valuation increases. From the shareholders’ point of view, this is bad even if the ability to fund charity signals current profits. What about reactivity? This part is easy to explain. Executives have many reasons to make philanthropic contributions, including the obvious one that they personally want to make societal contributions using firm resources. But executives also know that they are monitored by shareholders and financial analysts. If their contributions are so high that they are labeled as “nice” by a ratings agency, they may be targeted as acting contrary to shareholder interests. It is much better to make contributions that are small enough to be below the radar, so they react by reducing contributions. It may seem like a reverse form of impression management that executives try to avoid a high rating of the firm, but it simply reveals that the most important audience for impression management is shareholders. How big and important were these effects? Quite big. The ratings agency studied was KLD, which is a major rater of firm social contributions. Following a positive rating, firms reduced their philanthropic contributions by about one-half of a percent of profits, which is one-third of the average difference between firms rated positively and firms not given a positive rating by KLD. Simply put, the firms reduced contributions exactly as much as needed to become rated as less charitable the next year. We know that firm decision makers care about their reputation, engage in impression management, and pay attention to ratings. To observe reactivity like this is a clear signal that we do not yet live in an ideal world in which firms can divide attention between profits and ESG criteria, and we do not even know whether we are moving in that direction. Time will tell. Lewis, Ben W., W. Chad Carlos. Avoiding the Appearance of Virtue: Reactivity to Corporate Social Responsibility Ratings in an Era of Shareholder Primacy. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Gender pay gap disparity – paying women less than men for comparable work – is widespread and unfair, and much attention is given to how to remove it. Perhaps the most prominent option is to require pay gap disclosure, so that firms paying women less will be revealed and their reputation harmed. The idea is of course that two things will happen – firms will act to improve their reputation through paying women more, and female job applicants are warned and can stay away from these firms until conditions improve. The US has been reluctant to mandate transparency, but thanks to pay transparency laws elsewhere, we now know more about its effects. In a recent publication in Administrative Science Quarterly, Amanda Sharkey, Elizabeth Pontikes, and Greta Hsu studied the effects of mandated publication of the gender pay gap in the United Kingdom. One piece of good news: firms with pay parity received a temporary improvement in employee evaluations when that information was made public. One piece of bad news: that was the only good news. In particular, firms with pay disparity showed no observable short- or long-term decline in employee evaluations, and hence suffered no reputation loss either. Failing to find an effect was not a result of data problems; nor was it inconsequential. The authors were analyzing Glassdoor evaluations, which are reviews of each firm anonymously posted by its employees. Each evaluation is accurately timed, so it is easy to match the evaluation with the disclosure of the pay gap. The evaluations are consequential because many potential job seekers check Glassdoor reviews, both the numeric evaluations and the written text. This is a puzzle, and Sharkey, Pontikes, and Hsu proceeded to look for explanations. Interestingly, although some explanations could be excluded, not a single explanation could account for the failure to shame the firms with a pay gap. Part of the reason is that there are simply too many possible explanations, and they probably work together to make this happen. Because they add up to letting firms get away with unfair payment, it is worthwhile listing three explanations as warnings. Pay attention! There is some evidence that employees don’t fully pay attention to the pay gap when assessing their own workplace. Extending that observation, it is fair to wonder whether potential job applicants pay enough attention too. Paying attention is the first protection against walking into a trap. Interpret information! There is some evidence that employees react less when the pay gap is obscured by job heterogeneity. That is natural, but also discouraging, because more deliberate and conscious interpretation would usually help them understand that they are in a pay disparity trap. Act on interpretation! There is some evidence of resignation, with employees not reacting to the pay gap because they have become used to it. That is exactly how traps work – people do not escape from them. The reason to list these warnings is that it is hard to think of any policy to reduce the pay gap disparity that would be more effective than disclosure. Organizations constantly need to recruit new employees, and they always worry about their ability to attract the best. Obviously so, because there is another pay gap that is much more logical and beneficial for the organization than the gender pay gap. There are few jobs in which the pay gap between the most and the least productive employee is so great that the organization does not care about employee quality. The most productive employee is usually so much better for so little extra pay that having all the potential stars apply – male and female – is a great benefit for the organization. If employees and job applicants pay attention, interpret information, and act on the interpretation, pay disparity would simply be too costly for the organization. Perhaps they will gradually learn to do so. Sharkey, Amanda, Elizabeth Pontikes, and Greta Hsu. 2022. "The Impact of Mandated Pay Gap Transparency on Firms’ Reputations as Employers." Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming Photo credit. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed