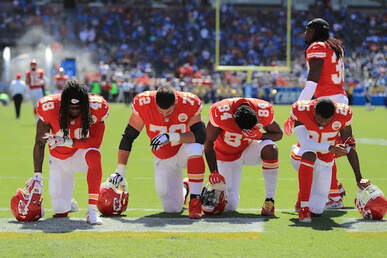

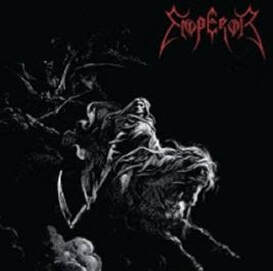

Let us talk about sexual abuse of minors for a moment. It is an uncomfortable topic, made even more uncomfortable by the fact that the sex abuse scandal in the U.S. Catholic church broke after two decades of sex abuse being known in communities and by the church. What happened? Knowing the answer is useful for protecting the vulnerable in society and for understanding how societies and communities interact. Recent research published by Alessandro Piazza and Julien Jourdan in Academy of Management Journal provides important answers. Their approach was intuitive and important. If members of the same large organization (the Church) are responsible for the same kind of abuse in many communities, but this is kept quiet in some communities but not in others, maybe it is valuable to find out what kind of communities protects the organization and lets its employees victimize its vulnerable members? What they found is depressingly familiar to anyone who studies organizations and communities. Communities who identify with the organization protect it – so although a majority Catholic community would have many more potential victims and families reporting abuse, a greater proportion of Catholics in the community actually protected the church against having misconduct made public. Well-organized communities also protected the Church. Many voluntary associations and informal meeting places indicate a community capable of much joint social action and self-improvement. In the case of abuse by local clergy, this positive community characteristic instead turned negative. Rather than acting to reveal the abuse, the communities showed inaction. Finally, community homogeneity also predicted communities that protected the abusers and the Church. Specifically, ethnic homogeneity (for example, nearly all White) was an indicator of communities that would be unlikely to making public cases of sex abuse. Why did this happen? Homogeneity, organization, and identification are characteristics of communities that are capable of a great deal of organized action, but in the abuse case, they instead seemed to display organized inaction. But let us not make a theory of grand conspiracies of communities against vulnerable members: a simpler explanation is probably correct. Speaking out is costly. It is especially costly when the complaints are sensitive, as in sex abuse. It is even more costly when the accusation is directed at a highly respected pillar of the community, as when the abuser is clergy. The costs increase when community homogeneity and organization create the suspicion (and often, reality) that others will organize against the whistle-blower, and when community identification with the organization makes such counter-organization a near certainty. So, parents would be quiet, journalists would not write stories, editors would not allocate space in newspapers, and the Church would quietly reassign and sometimes defrock the perpetrators. For decades. We need to understand this because the processes are general, and they can happen for similar or different kinds of abuse, and for similar or different organizations. Piazza, A., J. Jourdan. 2023. The Publicization of Organizational Misconduct: A Social Structural Approach. Academy of Management Journal forthcoming.  If you have visited France and are like me, you have been completely impressed by the amazing French bakeries. Truly artisanal artistry with a great lineup of baked goods. You likely have also failed to notice that there are two kinds of them. One is the original kind where the baker handles every step of the process. The other is a modern kind using pre-mixed flours and fixed recipes from one of a few major brands—in other words, French artisanal franchise breads and pastries. What makes this a case of competition across generations? That’s the topic of research by Laura Dupin and Filippo Carlo Wezel published in Administrative Science Quarterly. The idea is that both kinds of bakeries make the same kinds of goods, but the modern kind is standardized across locations rather than unique. Why should customers – and bakers – care about the difference? Well, the customers may be better at tasting the difference than I am. And the bakers may care more, because the modern kind know that they are giving up uniqueness and “personality” for an easier way of doing business. What does that mean for competition? Bakeries are the kinds of businesses that care deeply about location, because the business (at least in France) involves the baker getting up crazy early to make breakfast-style goods, which nearby customers buy and carry home or to work. I have certainly walked past bakeries in France to get to a better one farther away, but there are limits to how far I will walk, and there are also limits to how far a local customer will walk. So, bakers want to be near to customers, and they may also want to be away from each other. Bakers also think of how distinctive they are, and that’s where things get interesting. The modern style think they are less distinctive because, well, they are less distinctive. The traditional ones think they are more distinctive. That introduces an interesting dynamic. The modern kind wants to be located away from all others and, if possible, in the same place as an earlier (failed) modern kind. The traditional baker is more likely to be fine with locating near a modern one because they know they are distinctive and think that gives them an advantage. Does this matter for other kinds of businesses? It should. Customization gives distinctiveness, and so do brand names. As goods move around more and more easily, industries become “nearer” all the time. In the modern age of easy comparison of products on platforms and in online reviews, the branded good may become more powerful than ever. Dupin, Laura and Filippo Carlo Wezel. 2023. Artisanal or Half-Baked? Competing Collective Identities and Location Choice among French Bakeries. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Consider this combination of factors: a woman employee works in an organization with a gender equality initiative, and she even has a woman manager. Is this the best possible situation? No, it is not. And the explanation has nothing to do with queen bees. Instead, the problem is that women managers are, well, women, and their experience with discrimination has left a trace in how they work and interact with others. This is, in brief, the finding of research by Vanessa M. Conzon recently published in Administrative Science Quarterly. She studied an organization with a science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) business and staffing, which is one more reason why a gender equality initiative should go well, given the high education and liberal values of many employees in STEM organizations. Yet, this organization displayed a paradoxical divide: women managers spoke more clearly in support of a flexible work policy that made space for maternity leave and onsite childcare, but it was the men managers who more often let the women employees use this policy. Why? Conzon discovered that the underlying reason was that men and women managers differed in the work they had been allowed and expected to do, and the resulting work habits. For men, there were two paths: dive into technological expertise, or dive into client relations. The two could be sequenced, with technology first, or they could be combined. Promotions followed their success in handling these assignments. For women, the most open path was one of handling administration and coordination, often done despite their technical skills and overlooking their potential client-handling skills. Promotions followed their success in supporting coworkers and subordinates. These gendered career paths shaped how they interacted with subordinates and what they allowed subordinates to do. Men thrived in their technical and client-facing roles regardless of the work schedules of their employees, and they coordinated their employees from afar with email as the main tool. Women required employees’ presence to coordinate and support them, and to some degree even to make sure employees did what they were told to do. Although a manager was still a manager, man or woman, an undercurrent in the firm was that subordinates followed men managers’ instructions more faithfully than women managers’ instructions. The result was a flexible work policy that had very different consequences for men and women managers. For the men managers, the policy mattered little because employees would still do as they were told roughly when they were supposed to, and it mattered little how they scheduled their work hours or whether they worked at home or in the office. For women managers, employees’ use of the flexible work policy meant that the valuable face time would be reduced and become unpredictable, making the managers’ job harder. So yes, support for such a policy is good – but to see who will actually make it happen, we should also consider who benefits from the policy, and who is damaged by it. Conzon, Vanessa M. 2023. The Equality Policy Paradox: Gender Differences in How Managers Implement Gender Equality-Related Policies. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Do you know music theory? Most people studying organizations or managing organizations do not, but maybe that should change. Organizations improve by learning, and a large part of this learning is done by teams. For example, teams are used to drive innovation efforts or more incremental problem-solving or improvement efforts. That is why Administrative Science Quarterly has published an article by Jean-François Harvey, Johnathan Cromwell, Kevin Johnson, and Amy Edmondson using music theory to understand the innovativeness of teams. They followed central principles of music theory, connecting the various ways teams can learn with the principles of tonality, harmony, and rhythm. If this sounds unusual, maybe a look at the details helps? Tonality is the overall arrangement of a musical piece, and the main component is the tonal note, which repeats and supports the rest. For team learning to have tonality, it needs to use a repeatable form of learning with predictable results. Among the different learning approaches, learning from own experience provides tonality, which makes it necessary, but it needs to be combined with other approaches to produce innovation. That is where harmony comes into play. Some learning approaches may have harmony with learning from own experience and can be done simultaneously with it. Specifically, learning from the experience of others is harmonious because it has a similar goal of relatively incremental innovations; it just has different and less predictable results because it is harder to tell what information others can provide. But what happens when teams employ other types of learning that may not be in harmony with learning from one’s own experience? This is when rhythm is crucial. In music, tension can be built by changing between harmony and disharmony over time. The crucial phrase here is “over time.” When teams move from sequences of harmonious learning to disharmonious learning events – such as explorations through making experiments or seeking information from the context – doing so can be very productive if these experiences are spread across teamwork episodes. A team cannot innovate if there is too much harmony all the time, but it also struggles if there is too much conflict or dissonance within the same teamwork episode. Finding a learning rhythm by creating harmony and disharmony across teamwork episodes is key to improving performance. Does this sound overly elaborate and potentially speculative? Well, here is the really good news. All the theory described above was shown to hold both for innovative teams in a field study of an organization and during an experiment involving innovative teams. We all enjoy music, and most of us enjoy it without knowing much music theory. We also benefit from innovations, and some of us try to lead innovative teams. This new research may give all of us good reason to learn some music theory, to explore harmony and rhythm in teamwork, and to see how these lessons can improve organizational life. Harvey, Jean-François, Johnathan Cromwell, Kevin Johnson, and Amy Edmondson. 2023. The Dynamics of Team Learning: Harmony and Rhythm in Teamwork Arrangements for Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  We are in the middle of a major technological revolution, with large-scale language models such as GPT (and its app ChatGPT) making collecting information and reporting in the form of text immensely easier than it has ever been. If the early problems (like imprecision and untruths) can be worked out quickly, which seems likely, is that what the future will look like? Maybe so, but there are reasons to suggest that the needle can turn back to older technologies, such as persons typing on their computers. Let us not try to speculate about ChatGPT now, because it is in the future, but instead look at a lesson from a technological revolution in the past. Conveniently, Andrew Nelson, CallenAnthony, and Mary Tripsas just published research on a modern technologybecoming replaced by an older one in Administrative Science Quarterly. This is a technology that you are familiar with because you have heard it and possibly owned it too – the digital music synthesizer. It was the replacement of another technology that you have heard, but probably not owned because it was so hard to use – the analog music synthesizer. What is the difference? Technically the progress made by the digital synthesizer was that music is produced by translating a digital stream into sound (which is always analog), which in turn requires a digital processing device and allows the same processing device to use pre-programmed and stored sounds. Push a button to get a piano, or another analog instrument, or a sound not produced by any instrument. Analog synthesizers are analog all the way, which requires turning various knobs to produce the desired sound. The digital option is much, much easier to use and produces a great variety of sounds. Digital synthesizers still dominate the living rooms (or whatever other rooms) in people’s houses where children learn to play keyboards and aspire to become pianists. They are so flexible in use that they dominated the stages of bands too. But then, something happened. The great ease of using them meant that they leveled the field too much, made keyboardists sound too similar to each other, and made it harder to produce unique and personal sounds. This might not have been a problem for a digital technology doing surgery – we want reliable and reproducible surgery, not personally expressive surgery. But musicians are artists looking for unique expressions, stirring a demand for a return of the older, harder to use, but more expressive technology. What next? Digital technology is very advanced – it can skillfully pretend to be analog technology, and indeed digital synthesizers emulating analog ones soon appeared in the market and became popular. But in a world inhabited by members of a powerful occupation who require a technology to display their personal ability and expression, that could never be enough. So, the technology moved again to meet their requirements, concluding a cycle that ended up where it started. Or more accurately, these technologies coexist now, and what each musician chooses says a lot about who they are and what they are trying to accomplish. For the very elite, personal expression through adjusting all the knobs to produce just the right sound is the way to go. For the other layers, all the way down to the 4-year-olds discovering that they can play music, the ease of the digital synthesizer is still the convenient option. So if you are telling people that ChatGPT can never become a writer, keep in mind that there are many different kinds of writers with different needs. Maybe you will also become fascinated, find ChatGPT convenient for a while, and then go back. That just means that you are similar to the most ambitious musicians. Many others will be fine using the digital writing synthesizer. Nelson, Andrew, Callen Anthony, and MaryTripsas. 2023. “If I Could Turn Back Time”: Occupational Dynamics,Technological Trajectories, and the Reemergence of the Analog Music Synthesizer. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  For those of us who are not creative, it is difficult to imagine how creative people work. Perhaps we get some ideas from learning techniques such as brainstorming, when a team gets together and talk about ideas, with a ban on critique and an emphasis on letting each idea feed subsequent ideas. That’s a nice image, but it is not at all how creative industries and individuals work. Have you ever thought how unfair it is that the person with the messiest office is often the most creative at your workplace? Actually it is not unfair, and it is not just your workplace. The explanation for the messy creative person and the uncreative brainstorming session can be found in research by Poornika Ananth and Sarah Harvey published in Administrative Science Quarterly. They had a big study of creative individuals in theatre and architecture, and among their many findings two stood out. Creativity can be drawn from storage. Creativity can be stored. A key insight is that people who have creativity as their main work do not work on a single project, but many, both in sequence and concurrently. They get ideas and inspiration, which fuel creative outputs, but often these do not fit their current project well enough. What to do with ideas and inspiration that do not fit? Think about them creatively, create symbols that make them concrete and memorable, and store them for later. Try to make the storage systematic enough that they are easy to retrieve later. What to do with creative projects when no ideas and inspiration are coming? Go to the creativity storage and see what fits. Probably nothing fits exactly, but there will be pieces there that look almost right and can be cobbled together. Creative people, especially when working in creative industries, are good at their work exactly because they have a portfolio of stored creative inputs that they can use in their portfolio of creative projects. It is interesting how this description of creativity fits a theory of culture known as “culture as a toolkit.” When people have and use culture as a toolkit, culture is partly in their memory and partly picked up from others. They can have many cultural elements, which are not necessarily consistent with each other, and they will draw from those cultural elements to solve problems they encounter. The individual with a large and diverse cultural toolkit is a lot like the creative individual – a large storage of ideas and inspiration, and great ability to solve problems. Perhaps we should not be surprised? A lot of creativity is culturally judged, and some of it even creates culture. We learn from theatrical plays and from watching buildings, if they are creative. The creative individual who stores and retrieves ideas and inspiration also creates ideas and inspiration for us, and is doing society a great service. As I finish writing this, I am looking at my office, which is disturbingly tidy for a professor. I still like to think of myself as creative, and maybe it helps that my brain is messier than my office. I do have good memory, though, and I maintain a portfolio of projects that I work for. There is hope for everyone once we understand the processes that lead to creativity. Ananth, Poornika and Sarah Harvey. 2023. Ideas in the Space Between: Stockpiling and Processes for Managing Ideas in Developing a Creative Portfolio. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  We already know about CEOs making political statements using their firm as a tool – such as leaving California while protesting taxes and regulation, or publicly announcing that they will cover travel expenses for abortions for their employees in abortion-banning states. There is debate over how much CEOs should engage in political debates and use their firms to make statements. But what about employees? Of course, anyone is free to act politically outside work, but it is also possible to use the firm as a tool for public protest. Research by Alexandra Rheinhardt, Forrest Briscoe, and Aparna Joshi published in Administrative Science Quarterly asks when employees are more likely to use their organization as a tool for making political statements. It focuses on a public protest – the “Take a Knee” movement of players in the NFL (National Football League) kneeling or showing other kinds of protest during the pre-game play of the national anthem. It is a remarkably visible protest because of the TV broadcast of the event, the symbolism of the national anthem, and the clearly visible team uniforms. Some politicians, some team owners, and some audience members were aghast when this movement began – and many others were delighted. As any real form of protest should be, it was controversial, and it was also a powerful ingredient of the Black Lives Matter movement to protest racism and police violence. But what made some players in some teams join the movement, while others did not? The research found two factors that made the players more likely to use their team as a tool for public protest. The first was fairness – teams treating their players equally, as expressed through similar pay levels, were more likely to see players emboldened and making protests. Keep in mind that these were protests not against the team, but using the team colors, and they were protests for fairness in society. This makes sense. The second was openness – teams that were open to the message of the movement, as expressed through having a greater proportion of black players, were more likely to see their players protest. Again, this action is part of the Black Lives Matter movement, so it matters that a team does not specifically favor white players through its recruitment. This makes sense too. Both fairness and openness made individual players more likely to protest before a game, and it added up to making at least one player in the team, usually multiple, more likely to protest too. This brings us back to what happens when employees use the firm as a tool for public protest. Of course, it is a worthy effort for the employees, who feel strongly about the issue and want to express their views as publicly as possible. But should managers and owners be worried? That brings us to the last part of the story. Another item predicting protests was that the teams were in more liberal communities – communities that generally agreed with the Black Lives Movement and would likely react positively to players protesting on its behalf. At least in this context, one could argue that the player, by taking an overall controversial stance, brought the team closer to its community. For a move that received so much public attention – even with the president at the time (who has no particular authority on football team hiring decisions) telling teams to fire the protesters – this is an unusually happy ending. Rheinhardt, A., F. Briscoe, and A. Joshi. 2023 "Organization-as-Platform Activism: Theory and Evidence from the National Football League “Take a Knee” Movement." Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Here is a disturbing fact: The USA has had a little more than a million deaths from COVID-19, many of them unnecessary because of weak countermeasures – but since 1999, it has also had a million deaths from drug overdoses. Many of these are also unnecessary, because they involve drugs treating insomnia, anxiety, and in some cases pain. The drugs (benzodiazepines and opioids) can create dependence and are dangerous in high doses, so it is the doctor’s (physician’s) responsibility to check need and dosage. They often fail to do so, with deadly consequences for the patient. Finding out why this happens was the task of Victoria (Shu)Zhang, Aharon Cohen Mohliver, and Marissa King in research published in Administrative Science Quarterly. To get to the core of the problem, the researchers made two important innovations. The first innovation was to look carefully at how doctors are connected to each other through their patient sharing. Patient sharing means that the same patients see more than one doctor and implies that the doctors can communicate and learn from each other. Through their network of patient-sharing peer doctors, they can learn how to follow good practice, or they can learn how to deviate from it. The second innovation was to distinguish deviant (illegal) over-prescription from marginal over-prescription. Marginal over-prescription is when the doctor prescribes too much according to good practice, but not so much that it clearly violates legal limits. This is a liminal (borderline) practice, and accounts for more over-prescription than deviant over-prescription. Much more: 56 percent is liminal, as opposed to 9 percent deviant. The rest is by doctors who cannot be easily classified as either deviant or liminal. So how do doctors learn from their network? The answers are disturbing. Any kind of over-prescribing in the network (liminal or deviant) encourages any kind of over-prescribing by the doctor (liminal or deviant). Network misconduct promotes physician misconduct. So what distinguishes between doctors engaging in one or the other of these types of over-prescribing? It turns out that doctors with a central position (many connected peers) or a cohesive position (connected peers are connected to each other) were more likely to engage in deviant, criminal over-prescription. Looser connected network positions encouraged liminal over-prescription. What about doctors being more or less honest? We often think of people as being different in integrity and willingness to violate norms and break laws. We may even imagine that people differ in their tendencies to build networks depending on who they are. Part of the strength of this research is how carefully the researchers examined this explanation, finding that the network had strong effects even when accounting for many alternative explanations. Which is not to say that doctor differences don’t exist. In fact, high workloads led to much more liminal over-prescription but only a minor increase in deviant over-prescription. Illegal prescription was mostly related to age – young doctors or doctors near retirement age were more likely to do it. These are disturbing answers because they show that laws and norms are not enough. Laws regulate deviant/illegal over-prescription, but that accounts for a minority of the dangerous prescription. Norms are learnt, but findings on network effects show that the physicians learn liminal over-prescription just as well as normative best practice. And here is the most worrying part of the research, which I did not write until now. The patient-sharing networks the researchers measured were not captured through shared prescription of benzodiazepines or any other mental health drug—only regular drugs. This research shows that networks not organized around misconduct can produce misconduct learning. Zhang, Victoria (Shu), Aharon Cohen Mohliver, and MarissaKing. 2022. Where Is All the Deviance? Liminal Prescribing and the SocialNetworks Underlying the Prescription Drug Crisis. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Did you know that companies are full of would-be heroes? They are the managers of subunits, units, functions, and any other subdivisions of the company. They are doing their jobs, keeping their units efficient and fulfilling their goals, but what they really want is a crisis of some sort—a crisis that brings out their true potential as heroes who can make the necessary changes, right the course of the units they are managing, and prove that they should be promoted to greater responsibility. We like heroes. Companies promote heroes. But few ask the question of whether there are situations in which a hero creates loss for their company, even as they are trying to win by overcoming a crisis. Recent research by Julien Clement published in Administrative Science Quarterly looks at this question and finds some worrying answers. The context for drawing these insights is interesting, by the way, and explains the choice of hero in the illustration. He studies teams in the online game DOTA 2, which experienced multiple challenges due to rule changes. The start of the insights drawn from the research is that organizations are coordinated systems, so any attempt to change one unit can have consequences for other units. Change in one place usually makes the entire system a little worse, until corresponding changes are made elsewhere. When heroes do their work, they also put other heroes to work. That is only the start of the insights, though, and the continuation is worse. It is important to also ask why a crisis happens. Maybe it is because the hero’s particular unit experiences a local problem, for example related to the technology it operates, the inputs it gets, or the market for its outputs. But it could also be because of a system-wide problem that affects the entire company. If that happens, problems will occur in multiple units at once, and the changes to each unit will affect other units, creating a very confusing environment where it is hard to tell the difference between the original crisis and the new problems created by other units’ changes. When heroes go to work on the same problem and don’t coordinate, the problem can grow bigger. If heroes might lose, then what is the alternative? Simple. Any organization has a center, and when the entire organization is hit by a system-wide problem, the center needs to take charge. This is the time for a CEO and top management team to diagnose the system-wide problem and search for a solution. The system needs to change. Of course, the heroes can still be given work, but the task of each one should be defined and distributed centrally. (Notice how this explains why the Marvel heroes always struggle unreasonably much given their abilities – they are not centrally coordinated, but their adversary is.) The lesson for an organization is clear. The idea of operating it as an independent adaptive system is wonderful for the sequence of small and local challenges that constitute its daily life. At the same time, it is exactly the wrong approach for dealing with larger, system-wide problems that occasionally happen and sometimes spell the difference between success and failure. Clement, Julien. 2022. Missing the Forest for the Trees: Modular Search and Systemic Inertia as a Response to Environmental Change. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming.  Should we care about how firms use colors? That sounds like an unusual question, and I will soon give an even more unusual reason we now know something about the topic. Let me first suggest a reason to care, though: firms appear to be pretty conscious of color choices in logos. We may suspect that they rely on outside consultants and imitation quite a bit in selecting colors, of course. Notice how many web platforms and other IT firms seem to have a liking for various shades of blue (Microsoft Edge, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn) or have remarkably similar “rainbow” logos (Microsoft, Google, old Apple). So, they seem to care, but it is not clear that they think very independently about their color choices. How does that observation match our knowledge of color choices? Truth is, we know very little, but recent research by Stoyan V. Sgourev, Erik Aadland, and Giovanni Formilan published in Administrative Science Quarterly gives an interesting start. This research was not about Facebook, though, or any kind of firm: it was about the album covers of Norwegian black metal bands. This sounds somewhat unrelated to how firms choose colors, but if you stay with me a bit, we may be able to make a connection. The researchers showed that indeed color matters a lot for positioning, and in two ways. The first is that color is chosen with respect to peers. To position themselves initially, the black metal bands’ album covers primarily featured black (obviously) and other very dark or muted colors, and these color choices were influenced by peers’ choices. The second is that color is chosen with respect to the environment. Black metal bands were for a while under attack societally because of non-music activities such as church arson. Interestingly, their album cover design choices became less black during this time period, which made sense given a wish to dissociate themselves from news stories about crime and associated stigmatization. Although most firms are very different from black metal bands, we can suggest some connections. Colors do seem to indicate similarity with peers or competitors, so early choices of color by a group of similar firms or an industry probably matter a great deal. Color is also seen as symbolic, at least implicitly, and firms will pay attention to this symbolism. Exactly what symbolism is influencing the choice of blues by web platforms and other IT firms is not entirely clear to me, but blue does give an impression of cleanliness. (So does white, but white is not a practical color to use as a firm symbol on a computer screen.) We should also keep in mind that firms can be more strategic in color choices than the copying of color that we see so often. I mentioned that Apple, in its early years, had a rainbow logo similar to the logos currently used by Microsoft and Google. Its current color choice is different: Apple has been black, and it is currently grey. What does that mean? Interestingly, grey is also a color that gives a clean image, though it is arguably cooler than blue. It is also distinctive from the logos used by other firms with similar products and services. For Apple, that could be exactly the point: they have found one more feature shared by firms in the industry that Apple can use to show how unique they are. We still know little about colors. What we do know suggests that firms care about colors, but they tend to mimic each other. Mimicry does not indicate the most conscious of choices, but as Apple shows, it is possible to make independent choices that can be distinctive and smart. That is worth thinking about. Sgourev, Stoyan V. , Erik Aadland, and Giovanni Formilan. 2022. Relations in Aesthetic Space: How Color Enables Market Positioning. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming. |

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed