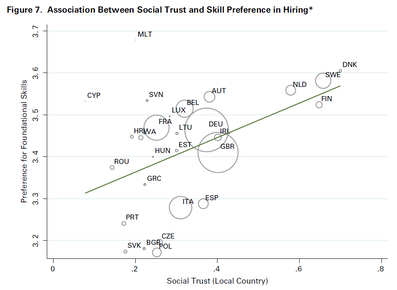

What is the relationship between trust and hiring? We all know the simple answer. Employers hire those who seem trustworthy, so trust and hiring are pretty much the same thing. But there is also a more complicated answer, and that one involves looking at how national cultures differ in the general trust levels. Suppose that two cultures differ in the level of trust – will employers in the high-trust culture hire more people than those in the low-trust culture? No, of course not, employers hire as many people as they need. But social trust levels still matter. How they matter is the topic of research by Letian Zhang and Shinan Wang published in Administrative Science Quarterly. It involves a novel idea and some nifty analysis, and fortunately it is easy to summarize. Trust does not mean hiring more people, but it does mean hiring different people. The reason is that low social trust is associated with hiring for a specific job, with less expectation that the employee can develop new skills. High social trust means hiring for the firm, with an expectation that the employee can develop new skills and fill other jobs. High trust, then, means hiring for foundational skills rather than advanced skills. It means hiring an analyst for general math ability more than for skills in Laplace transformations. This idea raises two questions. First, is it true? Using data on job postings from the European Union countries, Zhang and Wang found that it was indeed true. Employers in nations with high social trust hire based on more foundational skills than nations with low social trust. Moreover, the same multinational firm would hire more based on foundational skills in nations with high social trust than in nations with low social trust, so the same relation holds within employers as well. Job characteristics such as university education or work experience requirements reduced this effect but did not make it go away. Second question, is it consequential? Well, look at the figure above. Nations in Europe differ quite a bit in social trust levels, as the horizontal scale shows (the range is from zero to one). The vertical scale is not so easy to understand, but perhaps it helps to know that a difference of 0.6 is less than the difference between attentiveness and mathematics (foundational skills), and electricity principles and Java (advanced skills). The figure shows that the average hire in each nation differs significantly by the trust level. There are many possible consequences of these differences. We don’t yet know whether they all happen, but it is valuable to check each one. Hiring in high-trust nations means hiring for the long term and for multiple roles, giving greater room for personal growth and firm flexibility. Hiring in high-trust nations means less emphasis on specific expertise and credentials, so symbolic collection of certificates to get hired is unnecessary. Hiring in high-trust nations allows more diversity in teams doing a single task and better communication within teams, increasing creativity and productivity. Employers in low-trust nations may have lower access to all these benefits. We do not know whether all these differences result from different levels of societal trust. Now that we know how societal trust changes hiring practices, we should be aware that they might exist, and both employers and employees might think of employment practices and careers differently. Zhang, Letian and Shinan Wang. 2024. Trusting Talent: Cross-Country Differences inHiring. Administrative Science Quarterly, forthcoming. Comments are closed.

|

Blog's objectiveThis blog is devoted to discussions of how events in the news illustrate organizational research and can be explained by organizational theory. It is only updated when I have time to spare. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed